- THE ECB BLOG

More jobs but fewer working hours

7 June 2023

Unemployment has declined since the peak of the pandemic in August 2020, hitting a record low this April. But while more people have jobs, they are working fewer hours on average. In this post for The ECB Blog we shed light on this dichotomy and why it matters for the overall strength of the labour market.

One could look at the euro area labour market and see a success story. After an initial drop at the beginning of the pandemic, employment recovered quickly. Between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the fourth quarter of 2022, the number of people in jobs increased by 2.3%, which is quite impressive given how severe the economic shock was. It means that about 3.6 million more people found work during that time. But that is just one part of the story - a very important one, but one that offers an incomplete picture. It is worth looking behind those headline numbers and analyse how many hours those people in jobs are actually working. In other words, whether they have a full-time job or are working fewer hours than they would actually like. To that end, we distinguish between average hours worked (the average number of hours per worker) and total hours worked (for all people in employment).

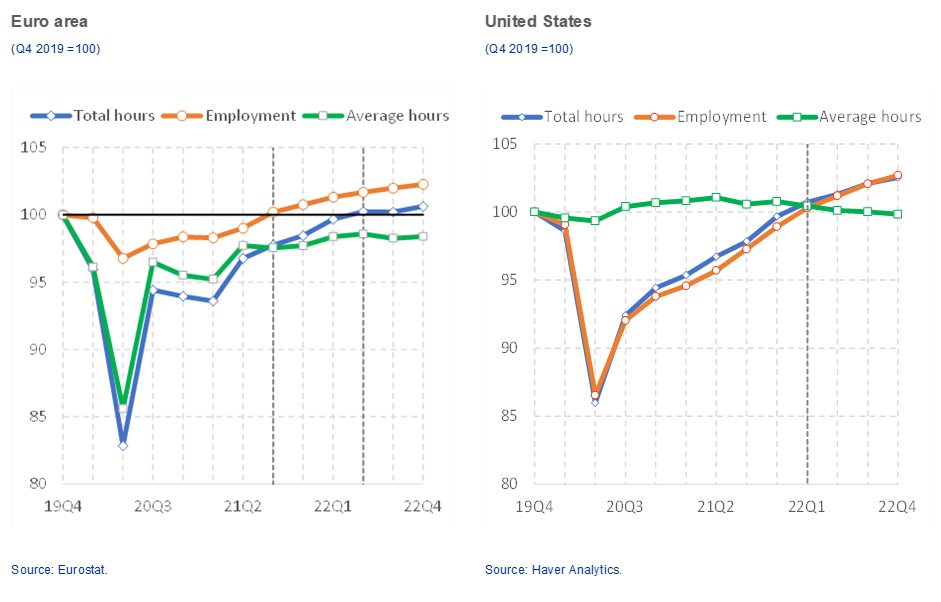

Over the period mentioned above, average hours worked declined by 1.6% (Chart 1, LHS). This represents a decline of around six hours per quarter and person since before the pandemic. The decline in average hours worked was particularly large at the onset of the pandemic, when government-supported job retention schemes facilitated the labour market adjustment as workers simply worked fewer hours (the so-called intensive margin). However, three years after the pandemic shock, average hours worked remain significantly subdued relative to employment, dampening the overall growth in total hours worked. But why?

Chart 1

Total hours and average hours worked

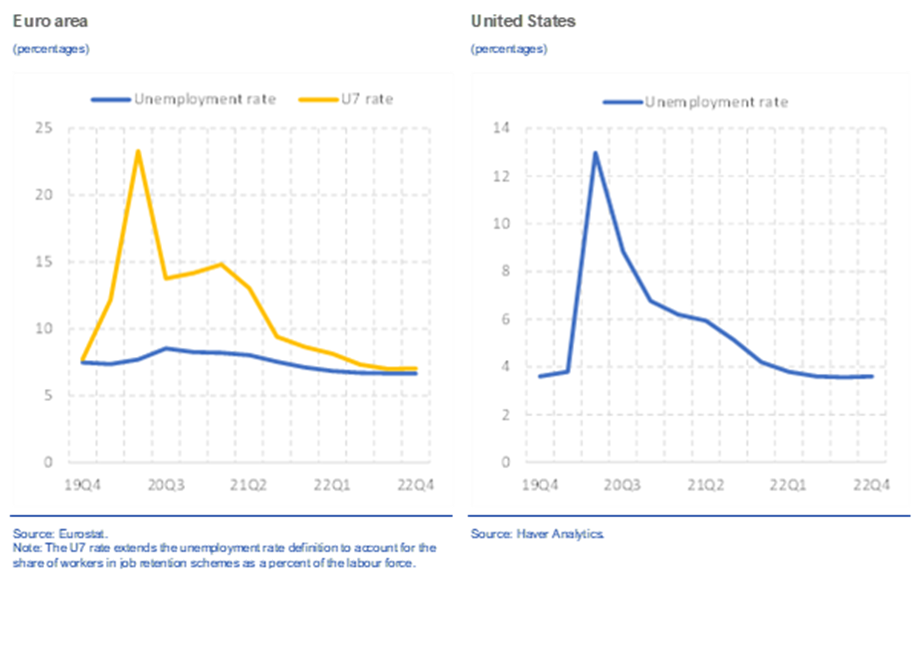

A comparison with the United States offers some interesting insights.[1] The two economies had similar adjustments in total hours at the onset of the pandemic (Chart 1). However, there is a stark difference in terms of average hours. While the adjustment in the euro area took place via the intensive margin (i.e. average hours worked) following the widespread use of government-supported job retention schemes[2], the changes in the US labour market did not affect average hours and occurred mostly via lay-offs (i.e. the extensive margin), resulting in much higher unemployment. This is also captured by the different developments in the unemployment rate in the euro area and the United States (see Chart 2). As the recovery took hold and fewer workers remained in job retention schemes, average hours worked in the euro area rebounded. Unlike the broadly stable path of average hours worked in the United States, however, they have stayed persistently below pre-crisis levels.

This naturally poses the question: what is driving the fall in average hours worked in the euro area at a time when many new jobs are created? Several factors stand out as potential explanations and are explored below.

Chart 2

Unemployment (and U7 for the euro area)

Construction and public services work fewer hours

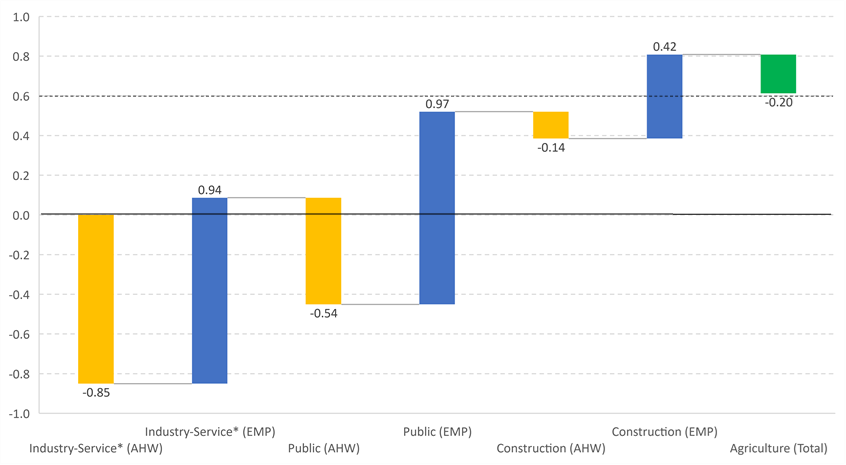

The moderate recovery of hours worked compared to employment varies significantly by sector. The lion’s share of the increase in employment has been in the public[3] and construction sectors: 1.5 percentage points out of 2.3% (Chart 3 – blue bars). This is 65% of the overall increase, even though the two sectors only make up about 30% of total employment.[4] The public sector, in particular, saw a smaller increase in hours worked compared to the strong increase in employment. Chart 3 shows the contributions to total hours worked across all sectors of the euro area economy, including both employment and average hours. Total hours did not increase much compared to pre-pandemic levels in the largest market sectors, such as industry (excluding construction) and market services.

Chart 3

Sectoral contributions to total hours worked

(cumulative growth, Q4 2019-Q4 2022)

Source: ECB staff calculations based on Eurostat data.

Note: Yellow bars refer to the sectoral contribution of average hours worked (AHW) to total hours. Blue bars refer to the contribution of employment growth (EMP) to total hours. The green bar displays the overall contribution from agriculture. Industry-Service* aggregate includes all industries and services expect for construction and public sector.

Labour hoarding

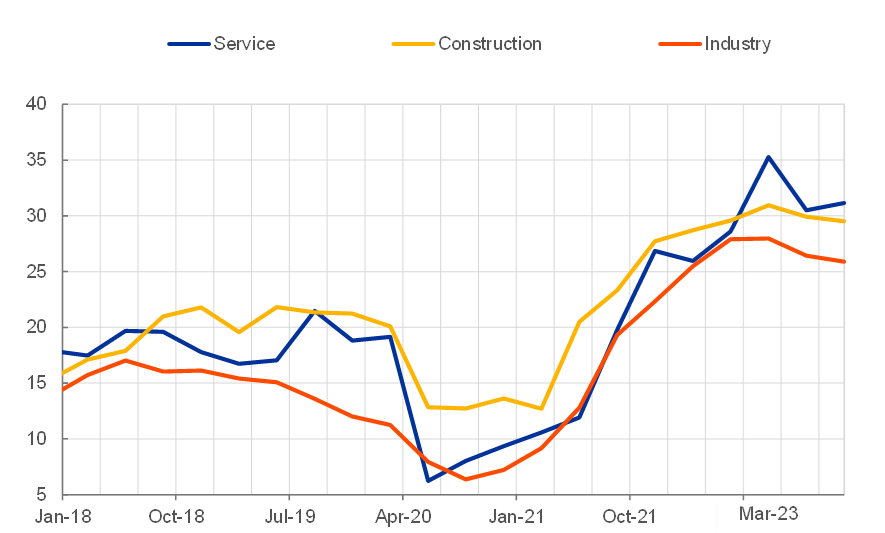

Labour hoarding may have continued to play a role beyond the most acute phase of the pandemic, although for different reasons than during the lockdowns. Average hours recovered substantially in 2021 and early 2022. However, when the economy slowed in the second half of 2022 as a response to the energy price shock and uncertainties relating to the economic fallout from the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine, average hours worked stagnated while employment continued to increase at robust rates. Firms were reluctant to let workers go despite the economic headwinds, especially skilled employees who would be needed in future.[5] Labour hoarding may be rationalised by the current tightness in the labour market, with job vacancy rates at a record high and the unemployment rate at a record low. Around 29% of firms report labour as a factor limiting production, comparing to about 17% before the pandemic (Chart 4).

Chart 4

Labour shortages across sectors

(percentage of firms)

Source: European Commission, Business and Consumer Survey.

Note: Labour shortages are defined as the percentage of firms replying that labour is a factor limiting production.

More workers are on sick leave

While average hours worked increased between the second half of 2021 and 2022, unusually high levels of sick leave have had a significant impact in the euro area. Various national sources from the four largest euro area countries suggest that sick leave has increased by between 10-30% compared to 2021. Most cases are temporary sick leave, meaning that employees remain on the payroll of their employers. Data for Germany suggest that average annual working hours lost due to sick leave increased from 68 to 91 between 2021 and 2022. This is about 1.8% of average hours worked in 2022.[6] Figures from sources for France, Italy and Spain[7] show a similar trend, although to different extent. This has amplified the impact of labour supply constraints at a time of both strong labour demand and easing global supply-chain bottlenecks.

Secular drivers

Pandemic-related factors notwithstanding, average hours worked in the euro area have followed a long-term declining trend driven by demographic factors and persistent reallocation of employment across sectors.[8] Yearly average hours worked declined by 6.8% between 1995 and 2019, from 1,686 to 1,571. The strong increase in part-time employment accounts for 80% of the decline in average hours until 2014. The increased share of women employed accounts for 16% of the decline in weekly hours (women work an average of 32 hours while men average around 39).[9] While a large part of the decline may reflect workers’ preferences – e.g. an increase in leisure time – not all of it may be voluntary. Recent evidence from the ECB Consumer Expectations Survey shows that whereas about 20% of workers would like to work fewer hours, 35% of workers would like to work more. In addition, while the number of part-time workers who wished to work more hours has declined since 2019, there were still about five million at the end of 2022 of which about 28% were low-skilled workers and 43% were middle-skilled workers.

Conclusions

The euro area labour market has shown remarkable resilience during the post-pandemic recovery. This was particularly visible in terms of the record high of more than 165 million people in employment at the end of 2022. The rate of participation in the labour market for some important sociodemographic groups, like women and workers older than 55, still has some room to increase. Moreover, as the inflow of foreign workers continues in the coming years the labour supply should keep on growing. And this will contribute decisively to the growth potential and the economic welfare of the euro area.

The subdued path of average hours worked, however, is dampening the vibrant recovery in headline employment figures and, possibly, adding to current labour scarcity concerns held by many firms. Some of the factors for this are likely to dissipate as the economy normalises following the recent sequence of adverse supply shocks and as current sectoral supply-demand imbalances ease. Hoarding labour may become less attractive for firms faced by rising labour and financial costs, leading to a normalisation of average hours worked. The recent increase in sick leave may revert[10] although it is still too early to say for sure. Other factors like the lower level of average hours worked in the public sector, however, may remain. In any case, the large number of people who wish to work more hours calls for an in-depth revision of potential obstacles in the institutional frameworks of euro area labour markets, which may be hindering individual and social benefits.

The views expressed in each blog entry are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the European Central Bank and the Eurosystem.

See Box 1 "Comparing labour market developments in the euro area and the United States and their impact on wages" in article "Wage developments and their determinants since the start of the pandemic", ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 8/2022.

Differently from the Global Financial Crisis, these schemes were widely used across all euro area countries, helping employed workers to keep their employment status even if they worked zero hours.

We consider public employment to be all employment in activity sectors O to Q according to the classification used in Eurostat’s EU Labour Force Survey, namely public administration, defence, education, human health and social work activities.

Public and construction sectors account for about 25% and 6% of employment, respectively. See “The role of public employment during the COVID-19 crisis”, ECB Economic Bulletin Box, Issue 6/2022.

See "Main findings from the ECB’s recent contacts with non-financial companies", ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 1/2023.

German Institute of Employment Research (IAB).

Information from national social security agencies (INSEE for France, INPS for Italy and Seguridad Social for Spain). In France, the number of employees with at least one day of sick leave is reported to have increased by about 11% from 2021 to 2022. The total number of sick leave days in Italy increased by 34% in 2022 compared to the previous year. Information for sick leave in Spain points to a 30% increase in average monthly sick leave per employee in 2022 compared to 2021.

See “Hours worked in the euro area”, ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 6/2021.

Eurostat Labour Force Survey data show that between 2002Q2 and 2013Q2 the share of part-time hours increased from 16% to 22%. Since then the share of part-time employment has stabilised, and even decline during the pandemic, meaning that the fall in weekly hours worked comes from full-time employment. The share of women in employment (aged 15-64) increased from 42.7% in 2002Q2 to 46.1% in 2013Q2 and 46.7% in 2022Q2.

Regarding the cyclical pattern of sick leave see e.g. Pichler, S. (2015), “Sickness Absence, Moral Hazard, and the Business Cycle”. Health Economics, 24, 692–710.