Drivers of firms’ loan demand in the euro area – what has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 5/2020.

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic is having multiple impacts on firms’ business plans and financing needs. In view of the importance of bank borrowing for euro area firms,[1] the euro area bank lending survey (BLS) is a rich and unique source of soft information not only on bank lending conditions, but also on the financing needs of firms.[2] When combined with hard economic and financial data, information from the BLS helps to explain developments in firms’ business plans and financing needs, as well as the driving factors behind them.[3] This box starts by discussing the long-term relationship between survey indicators from the BLS and actual developments in business investment. It goes on to examine the recent surge in firms’ demand for loans, the driving factors and the link with firms’ use of financing, in particular fixed investment, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, the box provides further details on this issue from a sectoral perspective.

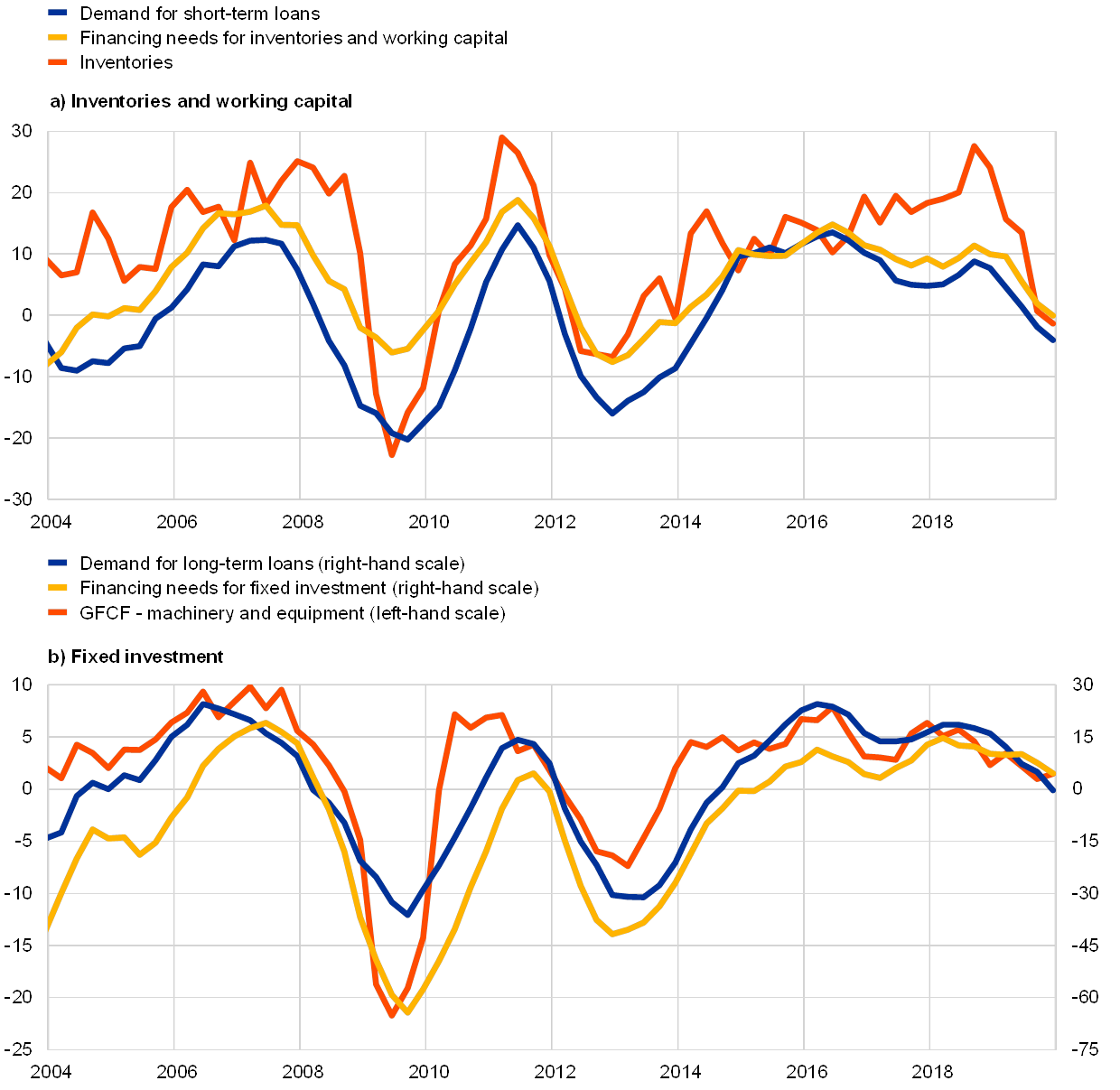

BLS data on firms’ demand for long-term loans and financing needs for fixed investment offer valuable and timely information on actual developments in firms’ fixed investment, given the strong correlation that exists between these variables. Empirical evidence shows that qualitative indications from banks on firms’ loan demand generally correlate well with actual developments in economic variables (see Chart A). In particular, there is a close relationship between the maturity of the loan,[4] the drivers of loan demand and the purpose for which the loan is intended to be used. For example, demand for short-term loans according to the BLS and the associated financing needs for working capital correlate well with actual developments in inventories. By the same token, long-term loan demand and the associated financing needs for fixed investment co-move closely with actual developments in gross fixed capital formation.[5] More precisely, a 1 net percentage point increase in firms’ financing needs for fixed investment is typically associated with an increase of about 0.3 percentage points in the annual growth rate of fixed investment. A more formal assessment highlights the informative value of the BLS indicator in nowcasting fixed investment. In particular, a model that also takes into account the BLS loan demand indicator in order to predict outturns in fixed investment leads to a significant improvement in accuracy compared with a naïve model that only contains past values of fixed investment.[6]

Chart A

Long-term relationship between firms’ financing needs and demand for loans

(panel (a): four-quarter moving average of net percentages of banks reporting an increase, EUR billions; panel (b): four-quarter moving average of net percentages of banks reporting an increase, annual percentage changes)

Sources: ECB (BLS) and Eurostat.

Notes: “Inventories” refers to changes in inventories and acquisition less disposals of valuables (Eurostat). “GFCF” stands for gross fixed capital formation (Eurostat). Demand for short-term loans and long-term loans, financing needs for inventories and working capital and financing needs for fixed investment are net percentages of banks indicating an increase or a positive impact on firms’ loan demand, based on the BLS. The latest observation is for the fourth quarter of 2019, i.e. before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

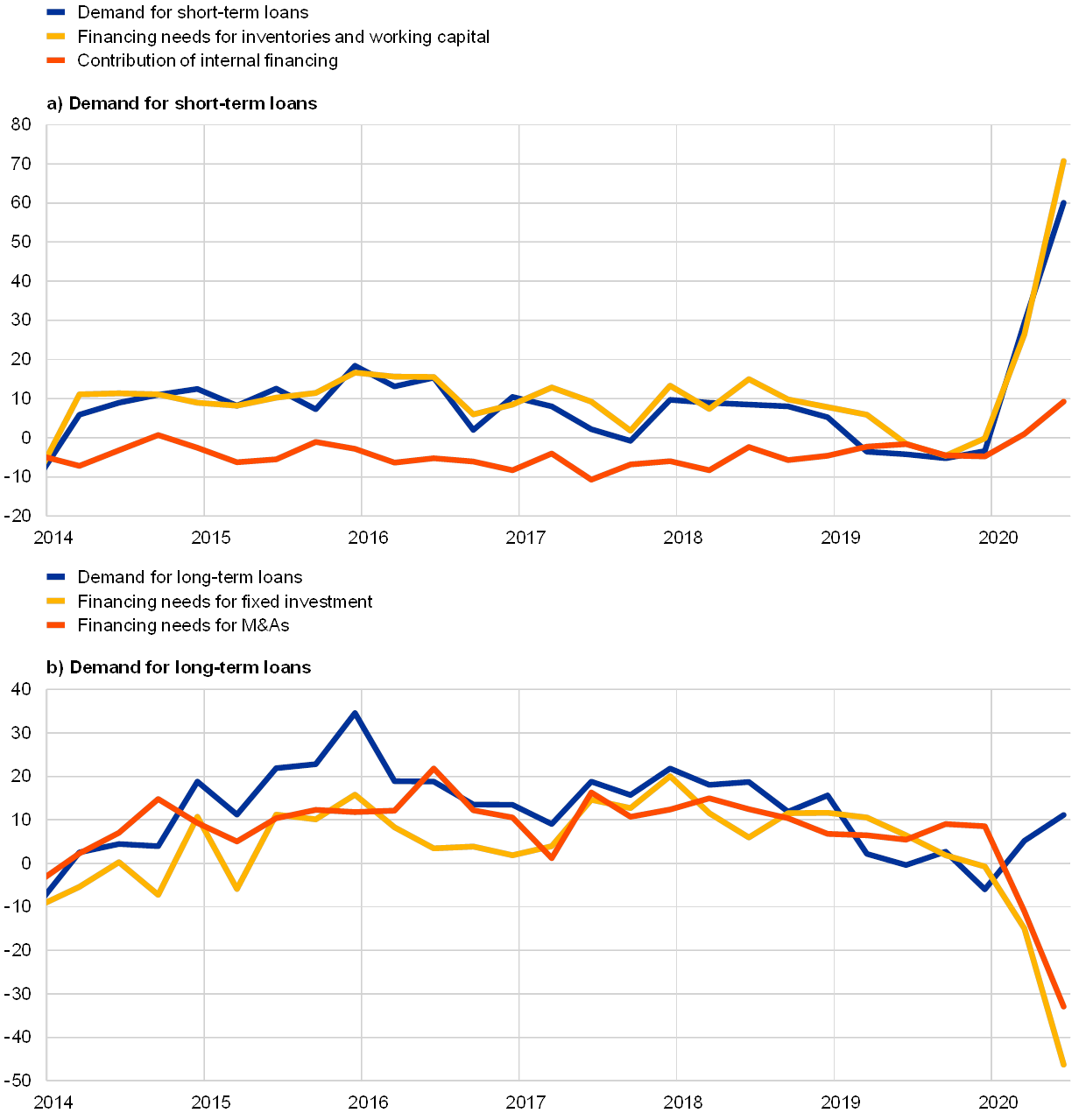

During the COVID-19 pandemic, this close connection between loan maturity and loan purpose has remained valid for the short-term maturity spectrum. The unprecedented nature of the pandemic led to a marked increase in the growth of loans to firms between March and May 2020 (see Chart 12 in this issue of the Economic Bulletin). Firms’ loan demand was fuelled by a decline in their capacity to finance their costs via cash flows, owing to a sharp fall in revenues during the pandemic. This situation resulted in acute liquidity needs to finance working capital (see Chart B, panel (a)).[7] Moreover, in an environment of high uncertainty, firms demanded loans with a view to building up precautionary liquidity buffers. Such acute liquidity needs were mainly associated with demand for short-term loans.

Chart B

Recent developments in firms’ financing needs and demand for loans

(net percentages of banks reporting an increase in loan demand, and contributing factors)

Source: ECB (BLS).

Notes: “M&As” stands for “mergers and acquisitions”. The latest observation is for the second quarter of 2020.

By contrast, firms’ demand for longer-term loans has decoupled from developments in fixed investment, reflecting the sizeable monetary and fiscal policy support measures put in place in response to the COVID-19 crisis. During the pandemic, the close relationship between loan maturity and loan purpose has been interrupted at the long-end of the maturity spectrum. While demand for longer-term loans expanded in the first half of the year, firms’ financing needs for fixed investment declined sharply (see Chart B, panel (b)). This substantial drop in financing needs for fixed investment was accompanied in the first quarter of 2020 by a steep fall in business investment, which is expected to intensify in the second quarter of the year.[8] This reflects either a reduction or a postponement of capital expenditure by firms, driven by the need to compensate revenue losses in a context of elevated uncertainty. At the same time, the rise in firms’ demand for longer-term loans has been bolstered by continued favourable credit standards for loans to firms[9] and historically low bank lending rates (see also Chart 13 in this issue of the Economic Bulletin), reflecting the sizeable monetary and fiscal policy support measures in place, in particular state guarantees on bank lending, which typically back longer-term loans. The perceived longer duration of the pandemic and the ensuing high degree of uncertainty have also contributed to the increase in firms’ demand for long-term borrowing.

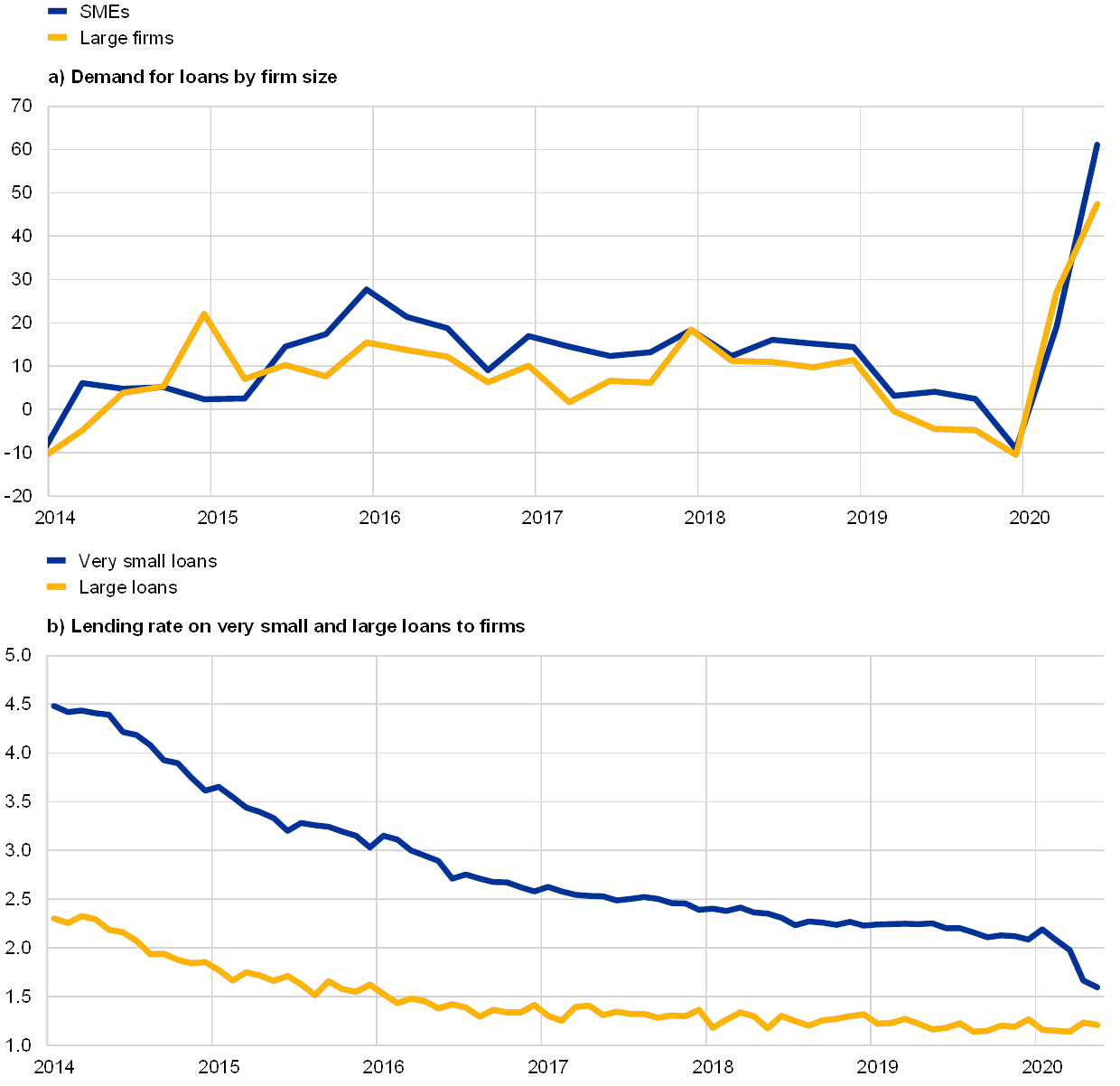

A comparison across firm sizes shows that the shift in the drivers of loan demand was more pronounced for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which have benefited substantially from policy support measures for bank lending during the pandemic. Loan demand increased more strongly for SMEs than for large firms in the second quarter of 2020, reflecting their greater dependence on banks for financing and emergency liquidity needs (see Chart C, panel (a)). At the same time, their high demand for loans has been met by banks at very low lending rates. In particular, at the euro area level, the difference between interest rates charged on very small loans (a proxy for loans to SMEs) and those charged on large loans has narrowed in recent months (see Chart C, panel (b)). This suggests that SMEs have benefited substantially from recent monetary policy measures supporting banks, such as the TLTRO III operations[10], as well as from state loan guarantees, which are typically targeted to this specific group of firms.

Chart C

Recent developments in demand for loans and lending rates by size

(panel (a): net percentages of banks reporting an increase in loan demand; panel (b): percentages per annum)

Sources: ECB (BLS) and ECB (monetary financial institution (MFI) interest rate statistics).

Notes: In panel (a), which is based on the BLS, the latest observation is for the second quarter of 2020. In panel (b), “very small loans” refers to loans of up to €0.25 million. “Large loans” refers to loans of over €1 million. The latest observation is for May 2020.

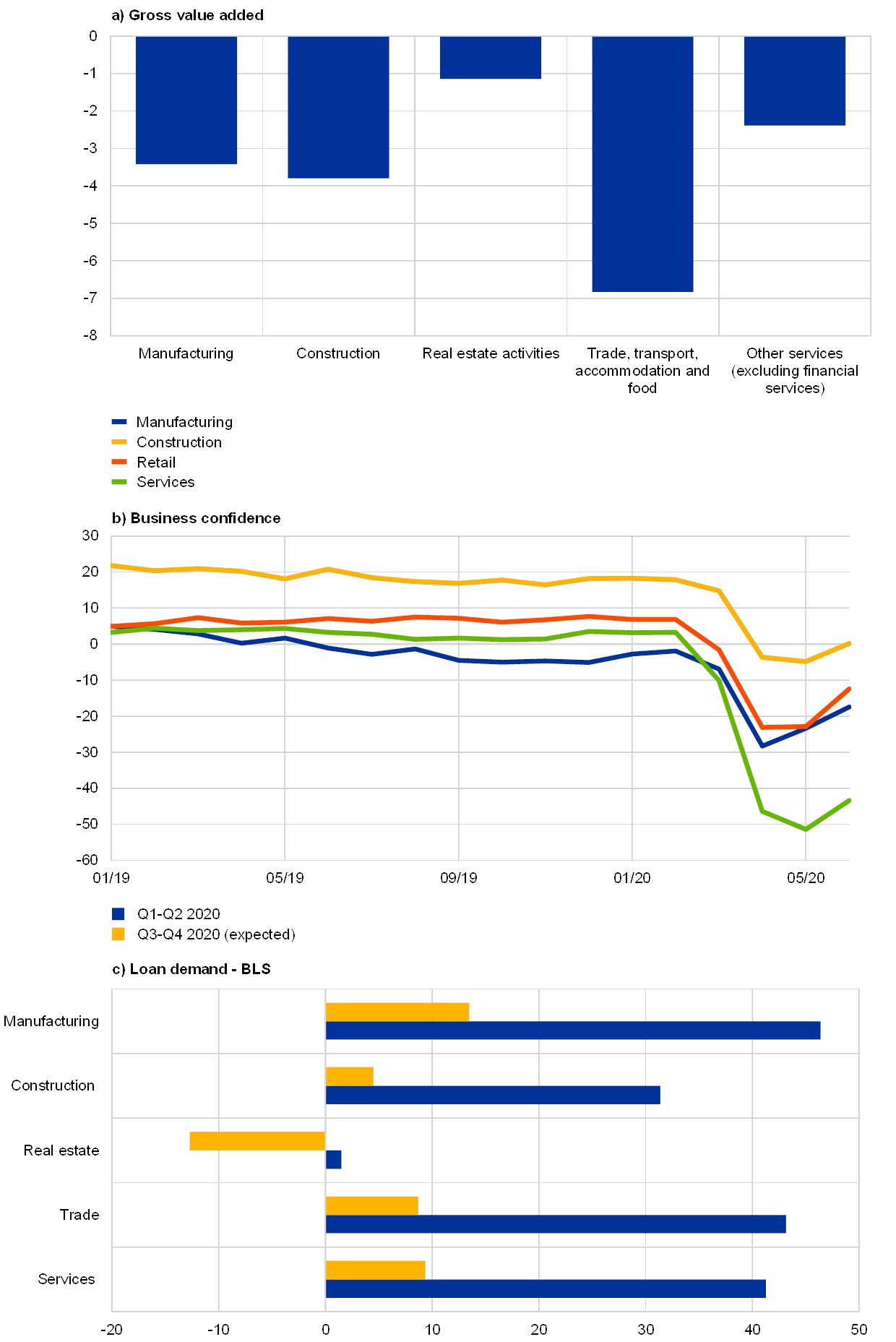

A comparison of financing needs across sectors shows that in the sectors most affected by the crisis, the demand for bank loans increased considerably, while value added dropped. The COVID-19 pandemic caused a larger loss of value added in trade, transport, accommodation and food service activities during the first quarter of 2020 than in manufacturing, construction and other sectors (see Chart D, panel (a)). In the second quarter of 2020, strict lockdowns, a lack of demand, interruptions to supply chains and high uncertainty are expected to have also reduced production significantly across large segments of the manufacturing sector, as reflected in a significant drop in business confidence in this sector (see Chart D, panel (b)).[11] In addition, further indicators, such as capacity utilisation and production in the capital goods sector, point to a strong decline in euro area investment in the second quarter of 2020.[12] Given the significance of the manufacturing sector in overall business investment, the decline in gross value added in this sector is likely to have been an important factor in the fall in business investment during the pandemic. Developments in sectoral activity are broadly in line with the latest evidence from the BLS, according to which, in the first half of the year, loan demand increased considerably in the manufacturing sector,[13] services sector (excluding financial services and real estate) and wholesale and retail trade sector (see Chart D, panel (c)). These data point to acute liquidity needs in these sectors. By contrast, loan demand increased less in the construction sector, and more particularly in the real estate sector, where firms have so far been less affected by the crisis. This can be attributed to the lower labour intensity and fixed costs of real estate activities, which resulted in smaller liquidity needs during the lockdown period.

Chart D

Gross value added, business confidence and demand for loans across sectors

(panel (a): percentage changes Q1 2020 versus Q4 2019; panel (b): percentage balances, deviation from long-term average; panel (c): net percentages of banks reporting an increase in loan demand)

Sources: ECB (BLS), Eurostat and European Commission.

Notes: In panel (b), “long-term average” refers to the period from 1999 onwards. Panel (c) shows net percentages of banks reporting an increase in loan demand in the July 2020 euro area bank lending survey (BLS). “Construction” refers to construction excluding real estate construction; “Real estate” refers to real estate construction and real estate activities; “Trade” refers to wholesale and retail trade; “Services” refers to services excluding financial services and real estate activities.

Given the significant risks weighing on firms’ bank financing, the continuation of monetary and fiscal policy support measures is crucial in ensuring a quick and robust recovery in business investment and economic activity. By preserving favourable bank lending conditions, the sizeable monetary and fiscal policy support measures in place have so far acted as a backstop against the risk of an adverse feedback loop between the real and financial sectors. In fact, the latest available survey data for June point to an improvement in production expectations and business confidence since the trough for the manufacturing sector in April, suggesting that some degree of recovery in investment activity is possible in the second half of 2020. However, the expected end of state guarantee schemes for loans to firms in some euro area countries in the coming months may lead to renewed fears about the creditworthiness of borrowers. In this context, the continuation of a supportive policy environment in the near future will be crucial in preserving favourable financing conditions and facilitating the flow of credit to the corporate sector. This would also improve the confidence that firms need in order to engage in long-term investment projects, on which a sustained recovery in economic activity depends.

- For more details, see the article entitled “Assessing bank lending to corporates in the euro area since 2014”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 1, ECB, 2020.

- See the ECB’s website for reports on the euro area bank lending survey. For more details on the BLS, see Köhler-Ulbrich, Petra, Hempell, Hannah S. and Scopel, Silvia, “The euro area bank lending survey”, Occasional Paper Series, No 179, ECB, September 2016, and the article entitled “What does the bank lending survey tell us about credit conditions for euro area firms?”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, ECB, 2019.

- Alternative survey indicators directly related to firms’ investment needs provide detailed complementary information but tend not to be available in a similarly timely fashion. See the box entitled “Business outlook surveys as indicators of euro area real business investment”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 1, ECB, 2020.

- Only two different maturities are used in the BLS, namely “short-term” and “long-term”. Short-term loans are loans with an original maturity of up to one year, while long-term loans are loans that have an original maturity of more than one year.

- Given the close contemporaneous relationship between fixed investment and banks’ indications on firms’ loan demand, both indicators have good leading properties (of about three quarters) with respect to loan growth. For more details on the cyclical properties of bank loans, see Darracq Pariès, Matthieu, Drahonsky, Anna-Camilla, Falagiarda, Matteo and Musso, Alberto, “Macroeconomic analysis of bank lending for monetary policy purposes”, Occasional Paper Series, forthcoming, ECB.

- The improved accuracy in nowcasting fixed investment is confirmed by a root mean square error gain of 19.85%. Standard analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests indicate that the superior in-sample predictive ability of the model augmented with the BLS indicator is highly statistically significant.

- See “The euro area bank lending survey – Second quarter of 2020”.

- The usefulness of banks’ qualitative indications on firms’ financing needs for fixed investment for nowcasting fixed investment developments therefore remains valid.

- See “The euro area bank lending survey – Second quarter of 2020”.

- For further analysis of the effectiveness of the ECB’s measures, see the box entitled “The impact of the ECB’s monetary policy measures taken in response to the COVID-19 crisis” in this issue of the Economic Bulletin.

- For more details on expected sectoral losses, see the box entitled “Alternative scenarios for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on economic activity in the euro area”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 3, ECB, 2020.

- See “Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area”, June 2020.

- In the case of manufacturing, loan demand was also driven by regulatory investment needs in the automotive sector.