Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 2/2024.

Forecasting inflation has been extremely challenging in recent years given the large shocks hitting the euro area economy. The extraordinary series of shocks seen post-2019 – including the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and Russia’s war against Ukraine – led to a surge in inflation. These shocks were exceptional in nature and so large in scale that assessing their transmission through the economy and into consumer prices in real time posed significant challenges. Importantly, several of the shocks were outside the historical distributions, severely limiting extrapolation from past patterns. In order to provide a better indication of the uncertainty involved, Eurosystem/ECB staff projections began setting out alternative scenarios during this period.[1]

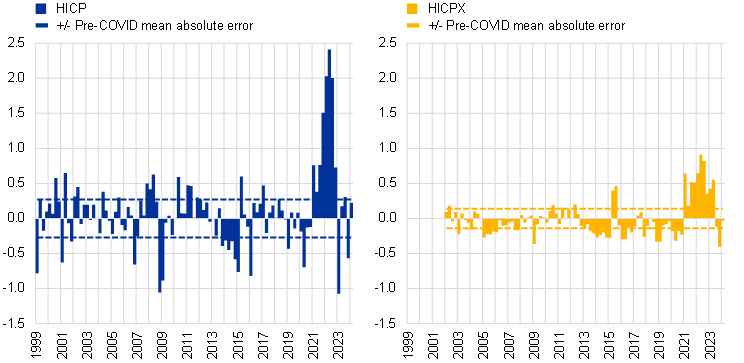

Errors in staff projections for short-term inflation increased as of the second half of 2021, before declining significantly in 2023. In 2022, the ECB published analysis of the reasons for the deterioration seen in the forecast performance of staff inflation projections as of mid-2021.[2] In 2023, further analysis took stock of the impact that the war in Ukraine and the resulting energy supply shocks had had on the accuracy of projections in 2022.[3] Those analyses emphasised the existence of large broad‑based errors in inflation projections – not only across forecasters, but also across economies. This highlighted the dominant role played by global factors in the context of the unprecedented spikes in commodity prices (especially for energy). However, the proportion of total projection errors that stemmed from energy commodity prices or other conditioning assumptions (as quantified by standard Eurosystem/ECB tools) declined in the course of 2022. This emphasised the role of other exceptional shocks, such as those stemming from the reopening of the economy post-pandemic and global supply chain bottlenecks, which mainly affected HICP inflation excluding food and energy (HICPX). The current box updates those analyses, focusing on the most recent period. Chart A plots one-quarter-ahead errors (calculated as the data outturn for a given quarter minus the relevant projection) for both HICP and HICPX inflation. It shows that the sharp deterioration observed in forecast performance lasted from mid-2021 until the beginning of 2023. Since then, the accuracy of staff projections has, broadly speaking, returned to the levels seen pre-COVID, especially for HICP inflation.[4] For HICPX inflation, the errors observed in 2023 were smaller, but still somewhat elevated by historical standards. Given the available data for the first two months of 2024, if inflation is assumed to remain unchanged in March 2024, that will result in a forecast error of ‑0.2 percentage points for HICP inflation in the first quarter of 2024, while the outturn for HICPX inflation will be in line with Eurosystem/ECB staff projections.

Chart A

One-quarter-ahead errors in the inflation projections of Eurosystem/ECB staff

(percentage points)

Sources: Eurosystem/ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area and Eurostat.

Notes: An error is defined as the outturn for a given quarter minus the projection made for that quarter in the previous quarter (for example, the outturn for the fourth quarter of 2022 minus the figure projected for that quarter in the September 2022 ECB staff macroeconomic projections). Data for the first quarter of 2024 represent average errors based on available published data (which only cover January and February 2024) and assume that inflation rates remain unchanged in March 2024.

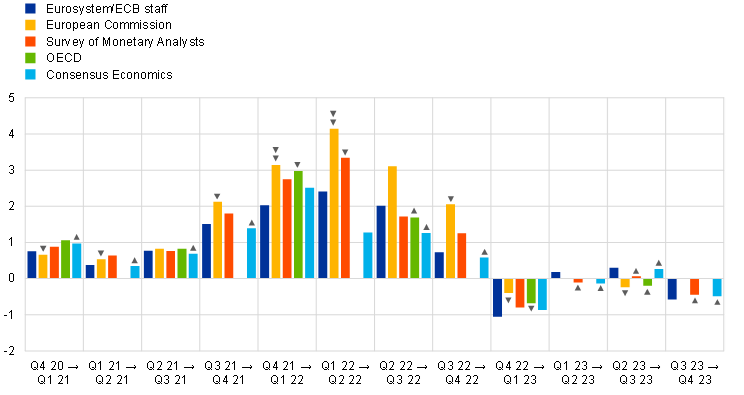

Euro area inflation forecasts produced by other international institutions and private forecasters have also improved in terms of accuracy over the last year. Projections made by Eurosystem/ECB staff and other forecasters have been very similar in terms of both the sign and the magnitude of forecast errors for short-term inflation (Chart B). When comparing such projections, it is important to account for differences in the publication dates of the various forecasts (which imply differences in terms of the information sets available to forecasters), as indicated by the arrows in Chart B. All major forecasters strongly under-predicted the surge in inflation in 2021-22, before being surprised by the speed of its decline in the first quarter of 2023, with considerably smaller and less systematic errors being observed since then.

Chart B

One-quarter-ahead errors in the HICP inflation projections of different forecasters

(percentage points)

Sources: Eurosystem/ECB staff projections, Consensus Economics, Survey of Monetary Analysts (SMA), European Commission, OECD and Eurostat.

Notes: Errors are calculated as the outturn minus the projection. The labels on the horizontal axis indicate the quarter in which the projections were published and the quarter to which those projections relate (i.e. “Q4 20 → Q1 21” denotes projections for the first quarter of 2021 that were published in the fourth quarter of 2020). For forecasters other than Eurosystem/ECB staff, errors are shown for publications with a cut-off date close to that of the relevant Eurosystem/ECB staff projections. For the SMA, data represent the median of survey respondents’ replies, while for Consensus Economics, data represent the mean. The arrows above/below the bars indicate differences in the number of months of HICP data that are available on the cut-off date for each publication relative to the Eurosystem/ECB staff projections: one upward arrow indicates one additional month of data, one downward arrow means one month less, and two downward arrows means two months less. Quarterly projections by the OECD are only available twice per year, so no errors are shown in the first and third quarters. As regards forecasts for the fourth quarter of 2023, the European Commission did not publish quarterly projections in its summer 2023 forecast, so no error is shown for that quarter. The cut‑off date for the September 2023 ECB staff projections was 30 August 2023. Although this was one day before the publication of the flash estimate of euro area HICP inflation in August 2023, flash releases for five euro area countries (covering 45% of total euro area HICP) were included, with the result that the figure used did not ultimately deviate from Eurostat’s flash release for headline HICP inflation.

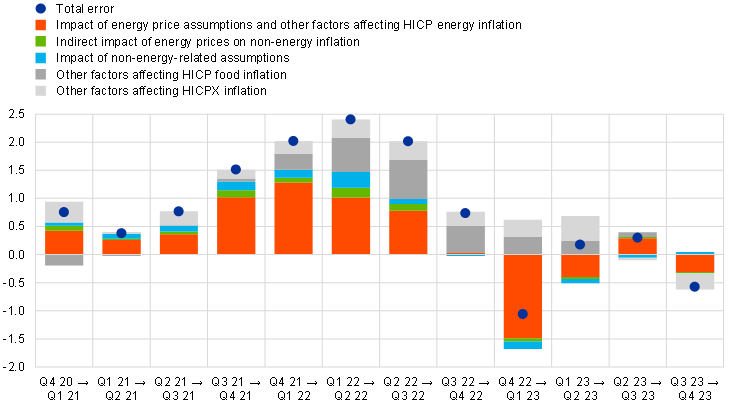

The drivers of projection errors have changed over time. Chart C breaks the projection errors for HICP inflation down by driver. Energy prices accounted for most of the errors up until the start of 2022. At that point, an unexpected surge in food prices also started to play an important role (as shown by the dark grey bars, which indicate, on the basis of standard elasticities, the contribution made by errors in HICP food inflation that are not explained by errors in assumptions).[5] Errors in HICPX inflation also had a considerable impact up to the second quarter of 2023. In 2023, energy prices began causing significant errors again, but this time it was the speed of their decline which was unexpected.

Chart C

Decomposition of recent one-quarter-ahead HICP inflation errors in Eurosystem/ECB staff projections

(percentage points)

Source: ECB calculations.

Notes: “Total error” is the outturn minus the projection. The labels on the horizontal axis indicate the quarter in which the projections were published and the quarter to which those projections relate (i.e. “Q4 20 → Q1 21” denotes projections for the first quarter of 2021 that were published in the fourth quarter of 2020). “Indirect impact of energy prices on non-energy inflation” is the sum of the indirect effects of oil, gas and electricity prices. For oil, these are based on the elasticities derived from Eurosystem staff macroeconomic models; and for gas and electricity, these assume an elasticity proportionate to the oil price shock. “Impact of non‑energy-related assumptions” relates to assumptions for short and long-term interest rates, stock market prices, foreign demand, competitors’ export prices, food prices and the exchange rate.

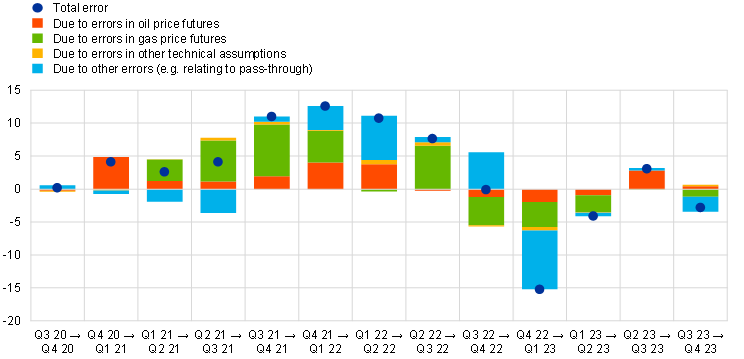

Initially, errors in assumptions regarding commodity prices explained most of the errors in HICP energy inflation, but later the increasingly complex nature of the pass‑through of energy prices began to play more of a role. When staff projections are produced, market expectations for several key variables (including those embedded in futures prices for energy commodities) are used as conditioning assumptions. In less exceptional times, these “technical assumptions” – particularly assumptions regarding oil prices – explain the vast majority of the errors seen when forecasting energy inflation.[6] As gas prices have increasingly become decoupled from oil prices, Eurosystem staff projection models have been updated to include gas prices as a distinct channel, separate from oil prices. Chart D provides a breakdown of the errors in energy inflation projections (mirroring the red bars shown in Chart C) on the basis of these adjusted models. In contrast to previous periods, oil prices have played a relatively limited role in explaining errors over recent years, while errors in conditioning assumptions for gas prices have been significant. Nevertheless, Chart D also shows that, even with perfect foresight regarding the paths of oil and gas commodity prices, the models would still have significantly under‑predicted energy inflation in 2022 and strongly over-predicted it in the first quarter of 2023 (as illustrated by the blue bars, which cover all errors not explained by technical assumptions). This probably reflects the complexity of price setting for consumer gas and electricity prices across euro area countries, which was compounded by extensive fiscal policy measures aimed at limiting the impact of the energy price shocks.[7] It may also reflect non-linearities in the pass-through from commodity prices to consumer prices, which may have been sizeable during this period.

Chart D

Decomposition of recent one-quarter-ahead HICP energy inflation errors in Eurosystem/ECB staff projections

(percentage points)

Source: ECB calculations.

Notes: “Total error” is the outturn minus the projection. The labels on the horizontal axis indicate the quarter in which the projections were published and the quarter to which those projections relate (i.e. “Q4 20 → Q1 21” denotes projections for the first quarter of 2021 that were published in the fourth quarter of 2020). The decomposition is based on updated elasticities derived from Eurosystem staff macroeconomic projection models as at late 2023.

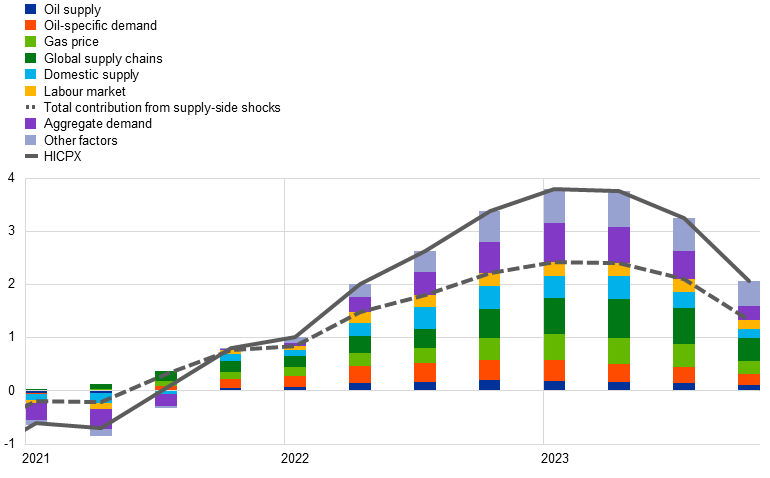

A historical decomposition of HICPX inflation confirms the large contribution made by indirect effects of the post-pandemic spikes in energy prices and hints at unprecedented transmission of those exceptionally large shocks. In the light of the unexpectedly strong increases in HICPX inflation in the recent past, ECB staff have developed a large structural BVAR model which identifies a wide range of demand and supply shocks.[8] A historical decomposition based on this model shows that the post-pandemic surge in HICPX inflation stemmed from a perfect storm of shocks (Chart E). Supply-side shocks – particularly indirect effects stemming from the unprecedented spikes in gas prices and disruption to global supply chains – accounted for most of the post-pandemic rise in HICPX inflation. However, demand shocks were also an important driver of those post‑pandemic dynamics, owing to the recovery in domestic and global demand following the reopening of the economy – albeit only from 2022 onwards. Following monetary policy action on the part of the ECB, the contribution made by aggregate demand shocks started to decline in 2023, helping the disinflation process. As Chart E shows, the share of total HICPX dynamics that cannot be explained by the model (labelled “other factors”) increases significantly from 2022 onwards. This could potentially point to a non-linear transmission of the large shocks seen in 2021 that cannot be captured by standard linear models. The evidence from this model demonstrates the importance of including indicators of global supply chains and gas prices when modelling and forecasting euro area inflation, as well as considering alternative modelling approaches.

Chart E

Model-based decomposition of HICPX inflation

(annual percentage changes; deviations from the mean implied by the model)

Sources: Eurostat and ECB calculations.

Notes: This chart shows the point-wise mean of the posterior distribution of the historical decomposition of HICPX inflation based on a large structural BVAR model with shocks identified using sign and zero restrictions. The last breakdown relates to the fourth quarter of 2023.

Although inflation projection errors have now returned to more normal levels, staff continue to refine their forecasting toolkits, providing additional analysis that can inform projections in times of high uncertainty. Staff continue to work on keeping their forecasting toolkits in line with state-of-the-art techniques and developing a more diverse set of models. This process is supported by regular exchanges within the Eurosystem’s technical forums and discussions with academics. One example of this is the more elaborate modelling of gas prices and global supply chains that is discussed above. Another example is the development of machine learning models that seek to capture some of the non-linearities mentioned above, with one such model being included in the suite of tools that staff use for regular cross‑checks of their baseline projections.[9] Moreover, staff also continue to develop tools aimed at assessing risks surrounding baseline scenarios, using a wide range of sensitivity analyses and alternative scenarios. Since March 2023, staff projections have been presented using fan charts, which highlight the uncertainty involved, especially at longer horizons.[10] Such additional analysis serves as an important input for the ECB’s monetary policy decisions, complementing the baseline projections and other analysis by staff.

In 2020 and 2021, each set of quarterly staff projections included scenario analyses based on alternative assumptions regarding the future evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic consequences. In 2022, alternative scenarios focused on the economic consequences of the war in Ukraine, especially as regards uncertainties about energy supply. More recently, the scenario analysis has focused on more specific risks, such as a slowdown in the Chinese economy or a potential escalation of the conflict in the Red Sea area.

See the box entitled “What explains recent errors in the inflation projections of Eurosystem and ECB staff?”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 3, ECB, 2022. See also the article entitled “The performance of the Eurosystem/ECB staff macroeconomic projections since the financial crisis”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 8, ECB, 2019. In addition, a full database of past Eurosystem/ECB staff macroeconomic projections is available to the public via the ECB Data Portal, which allows researchers to easily assess the performance of these projections. The processes and tools used to produce staff projections are described in a guide available on the ECB’s website.

See the box entitled “An updated assessment of short-term inflation projections by Eurosystem and ECB staff”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 1, ECB, 2023.

Similar developments can be observed at the four-quarter-ahead horizon. Four-quarter-ahead errors in HICP – and, to a lesser extent, HICPX – inflation also declined in 2023 and now stand close to pre‑pandemic levels.

See the box entitled “What were the drivers of euro area food price inflation over the last two years?” in this issue of the Economic Bulletin.

From the fourth quarter of 2001 to the fourth quarter of 2019 (i.e. pre-COVID), the median share of total one-quarter-ahead projection errors for HICP energy inflation that was explained by errors in oil price assumptions was about 90%; from the first quarter of 2020 to the fourth quarter of 2023, that median share was down to around 40%.

See the article entitled “Energy price developments in and out of the COVID-19 pandemic – from commodity prices to consumer prices”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 4, ECB, 2022; the box entitled “Climate-related policies in the Eurosystem/ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area and the macroeconomic impact of green fiscal measures”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 1, ECB, 2023; and the box entitled “Fiscal policy measures in response to the energy and inflation shock and climate change”, Economic Bulletin, Issue 1, ECB, 2024.

See Bańbura, M., Bobeica, E. and Martínez Hernández, C., “What drives core inflation? The role of supply shocks”, Working Paper Series, No 2875, ECB, 2023.

See Lenza, M., Moutachaker, I. and Paredes, J., “Density forecasts of inflation: a quantile regression forest approach”, Working Paper Series, No 2830, ECB, 2023.

See, for instance, Chart 4 in “ECB staff macroeconomic projections for the euro area”, March 2024.